| There

were two production of B&W ?Rubovian Legends?

marionette puppet plays. The first production, made in 1955,

consisted of just three plays, and was transmitted live from the

studio. Apart from one still photograph (printed in The Puppet

Master, June 1956), no recording exists of any of these. The

second production, which began in 1956 and lasted through 1965, is

the one remembered by most people familiar with ?Rubovian

Legends?. It consisted of twenty-six plays, two of which were

remakes from the first series.

The first production of three plays used

tiny (1/5 life-size) marionettes and scenery. The

marionettes were made by Kim Allen, borrowed

by Gordon from the BBC?s puppetry department. Settings and

costumes for the first two of these plays were

designed by Gordon Roland (The Queen?s Dragon) and Donald Horne

(Clocks and Blocks). No settings and costumes designer

credit was given for the third play (The Dragon?s

Hiccups), however, we do know that Rubovia designer Andrew

Brownfoot was involved with it, providing some new settings and a new

costume for the Queen.

The second production of twenty-six plays

used larger (1/3 life-size) puppets made by Gordon Murray for

which Andrew Brownfoot designed and made all the costumes and

scenery, with the assistance of his wife Margaret. Both

Andrew and Margaret were initially still studying Theatre Design at The Central School of Arts and Craft

in Holborn, but with encouragement from Jeanetta Cochranne, the Head of Theatre Design,

spent most of their time working for Gordon and the BBC.

|

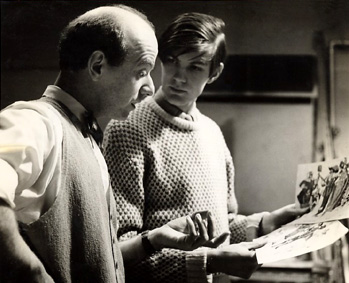

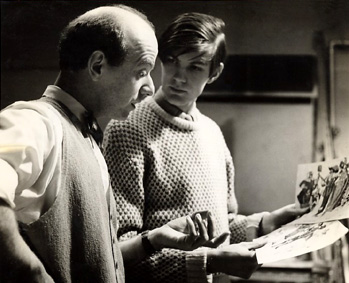

Gordon

Murray and Andrew Brownfoot discuss some of Andrew?s

costume designs for a non-Rubovian puppet play, The

Emperor?s New

Clothes. Tin Shed, 1959

Publicity

photo ? BBC

|

In the early days of

?Rubovian Legends? production, there were many challenges to be overcome.

For instance, there existed within the culture of the BBC, an

expectation that Gordon would use existing resources for scenery,

puppets, and costumes, etc. After starting with these, Gordon

quickly developed a very clear vision of what he wanted to

achieve, a vision that could not be confined within the limits of

what had already been done by others. His artistic vision required

a more advanced marionette puppetry format, with larger,

flexible-faced, moving-mouth puppets, professional voice-actors,

and larger scenery to match. He also needed to have artistic

freedom. In the end this was recognised by the BBC, and Gordon was

left to his own devices, which he loved. However this recognition

did not come with a budget to match, and so when Gordon needed a

sewing machine, money was tight and he was not able to requisition

one. As a result, unconventional solutions were the order of the

day. Gordon said in a 1959 interview (Puppets in a Hot Tin Shed,

by Roger Watkins, The Stage and Television Today, May 7, 1959,

p.12), ?I?ve broken every rule the BBC has ever made. Most of the things I do are highly

illegal?like buying a sewing machine on the petty cash, for instance. You just

mustn?t run up huge bills on the petty cash like I do.?

If the BBC was turning a blind eye to any of Gordon?s activities,

it was probably because his puppet plays were selling well

overseas, and were doing well in the UK as well. After the much

needed sewing machine was obtained, it was quickly put to good use by Andrew

Brownfoot, to make the intricate (1/3 life-size) miniature costumes for all of the puppets.

And when the petty cash would not extend to some need, Gordon

often bought it out of his own pocket. Such was his level of

dedication and desire to make the puppet productions the best that

they could be.

|

Andrew

Brownfoot?s

design for King Rufus of Rubovia, c. 1957

Illustration

courtesy of A. Brownfoot

(click

for larger image 70K) |

Looking around the

Tin Shed workshop area, the viewer would notice all sorts of materials which were needed on hand to create the world of Rubovia.

Liquid rubber for heads, plastics, moulds, paints, wood, glue, wire, the celebrated sewing machine, fabric, and props galore. An

exquisite four-foot-long model of Rubovia castle and its backdrop

of snowy mountains could easily catch your eye there, along with fancy fireplaces, four-poster beds,

all to Andrew Brownfoot?s designs in expanded polystyrene, a kind

of plastic so airy and light,

?that a puppet?s cough would blow it up the chimney.? (Come to the Puppet

Theatre! by Earnest Thomson, Supplement to Radio Times,

December 4th, 1959). In

fact you?d have seen pretty much anything one would expect to see gracing the interior of a

castle, such as miniature paintings, wall hangings, drapes, tiled

floors, Louis XIV style chairs and tables. Then there were props for the outdoor scenes as well, including anything related to Queen

Caroline?s famous

cabbage patch.

|

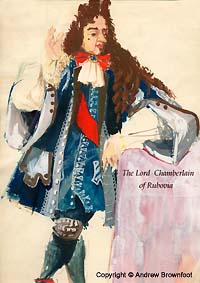

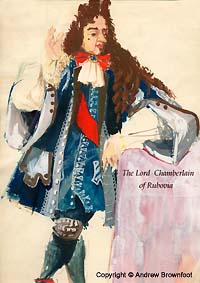

Andrew

Brownfoot?s

design for the Lord Chamberlain of Rubovia, c. 1957

Illustration

courtesy of A. Brownfoot

(click

for larger image 70K) |

Rubovia was very much a team effort. It

would go like this: Gordon gets an idea of what he wants to do and

tells Andrew who starts making rough designs of the costumes and

scenery. When they have agreed on how it should look, Gordon

starts work on making the puppets, Andrew builds the scenery and

makes the puppet costumes. When the puppets are completed, Andrew

paints their faces and Andrew?s wife Margaret assists with making

finishing touches such as make-up and styling the hair. The after

the puppets are dressed and Gordon has completed the script,

rehearsals start with the puppeteers. There was a large area available in the Tin Shed for this, which allowed for three puppet stages to be set up at the one time.

The first few ?Rubovian Legends? plays were sent out

live, in front of the television camera. On the day of

transmission, everything had to be taken down and then re-erected in the

television studio, in time for one or two last camera rehearsals

before the play went on air at 5:00 pm.

|

Andrew

Brownfoot?s

design for King Boris of Borsovia, c. 1957

Illustration

courtesy of A. Brownfoot

(click

for larger image 70K)

|

Live transmission was a very demanding and tense situation for all those involved. The puppets themselves were rather heavy, and

the movements required of them took considerable skill and strength. Now and then the unexpected occurred, such as a puppet falling over, or strings becoming tangled.

The technology of tele-recording had not been developed yet, and

nor was filming the norm, so there was no possibility of editing

out mistakes, and once the transmission was over, six weeks of

hard work were down the tubes, figuratively speaking. By 6:00 pm

the scenery was being torn down to make way for another

transmission, and everyone involved in the production would rush

over to the BBC club to wind down and recover from an extreme

sense of anticlimax.

|

Andrew

Brownfoot?s

design for Sir Albert Weatherspoon,

Royal Gardner at the court

of Rubovia, c. 1957

Illustration

courtesy of A. Brownfoot

(click

for larger image 62K)

|

Gordon said recently of Andrew Brownfoot

(July 2003) that he admired Andrew?s talent a lot, and was very

surprised and sometimes amazed at the wonderful costumes and sets

that Andrew had come up with at such a young age. Gordon added

that he had not expected a boy of seventeen to be so talented and

capable, doing things so well, even doing all his own research for

the costumes and sets.

Almost

fifty years after he painted them, Andrew Brownfoot's design

pictures of

the ?Rubovian Legends? characters still look as fresh as the day

the paint dried. The final look of the Rubovian puppets and their

costumes turned out quite close to these designs, the biggest

difference

being with King Boris of Borsovia, who developed from the original

conception somewhat. As recalled by Andrew (Dec 2003), ?In the

end, Boris was given a moustache and his cravat had a design of

horses heads, to make him look like a typical ?huntin?, shootin?,

and fishin?? type.?

|